A forgotten visual arts and cultural movement that thrived briefly between 1978 and 1983, Grupo Antillano articulated a vision of Cuban culture that privileged the importance of Africa and Afro-Caribbean influences in the formation of the Cuban nation. In contrast to the official characterization of Santeria and other African religious and cultural practices as primitive and counter-revolutionary during the so-called Quinquenio Gris (a "grey" period of neo-Stalinist censorship during the 1970s), Grupo Antillano valiantly proclaimed the centrality of African practices in national culture. They viewed Africa and the surrounding Caribbean not as a dead cultural heritage, but as a vibrant, ongoing and vital influence that continued to define what it means to be Cuban. Some Afro-Cuban intellectuals, such as the noted ethnomusicologist Rogelio Martínez Furé, proclaimed triumphantly that a "new," authentic Cuban art had been born.

Yet neither this "new art" nor the very existence of Grupo Antillano are remembered today. Grupo Antillano has been in fact erased from all accounts of the so-called "new Cuban art," a movement that took shape precisely during those years and that is frequently associated with the legendary exhibit Volumen Uno (1981). In contrast to Grupo Antillano, however, most of the artists of Volmen Uno did not look towards Africa or the Caribbean for inspiration, but to new trends in Western art. The "new art of Cuba," to use the title of art scholar Luis Camnitzer's famous book, came to be identified with the westernized approach of Volumen Uno, not with the Afro-Caribbean art of Grupo Antillano.

This exhibit seeks to recover the history of this group and their important contributions to the art of Cuba, the Caribbean and the African Diaspora. Several members of Grupo Antillano had attended the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) in Nigeria in 1977 and saw their work as part of a diasporic conversation on art, race and colonialism. As Group members stated in their foundational manifesto (1978), "The Antilles are our common real environment... We are not interested in other worlds." They saw their work as part of a long tradition of struggle, cultural affirmation and resistance, what a nineteenth-century Louisiana medical doctor had described as a slave disease: drapetomania. The main symptoms of this disease was an irresistible urge to run away and to escape slavery.

Essentially, these disparate artistic visions point to alternative interpretations of what it means to be Cuban and what constitutes a true national culture. This is, in other words, a debate about what Cuba should be, and how to handle the perennial problem of the country's racial diversity. This debate is particularly intense today, as different social and cultural actors seek to envision Cuba's possible futures and the roles of Cubans of African descent in those futures.

Grupo Antillano fue un movimiento cultural y artístico que prosperó brevemente entre 1978 y 1983 y que articuló una visión de la cultura cubana que destacaba la importancia de África y de los elementos afro-caribeños en la formación de la nación cubana. En contraste con la caracterización oficial de la Santería y de otras prácticas religiosas y culturales africanas como primitivas y contrarrevolucionarias durante el llamado Quinquenio Gris (un período caracterizado por la censura neo-estalinista durante la década de 1970), Grupo Antillano proclamó valientemente la centralidad de las prácticas africanas en la cultura nacional. Para los artistas e intelectuales de Antillano, África y el Caribe circundante no eran un patrimonio cultural muerto, sino influencias vivas y vitales que seguían definiendo el ser cubano. Algunos intelectuales afrocubanos, como el destacado etnomusicólogo Rogelio Martínez Furé, proclamaron triunfalmente el nacimiento de un arte cubano auténtico y "nuevo."

Sin embargo, ni ese arte "nuevo" ni la existencia misma de Grupo Antillano son recordados hoy. Grupo Antillano ha sido de hecho borrado de todos los análisis del llamado "nuevo arte cubano," un movimiento que tomó forma precisamente durante esos años y que se asocia frecuentemente con la legendaria exposición Volumen Uno (1981). En contraste con Grupo Antillano, sin embargo, la mayoría de los artistas de Volmen Uno no miraba hacia África o el Caribe en busca de inspiración, sino a las nuevas tendencias en el arte occidental. El "nuevo arte de Cuba," para usar el título del famoso libro del crítico de arte Luis Camnitzer, pasó a identificarse con Volumen Uno, no con el arte afrocaribeño de Grupo Antillano.

Esta exposición pretende recuperar la historia de este grupo y sus importantes contribuciones al arte de Cuba, el Caribe y la diáspora africana. Varios miembros de Grupo Antillano asistieron al Segundo Festival de las Artes y la Cultura de África y el Mundo Negro (FESTAC) en Nigeria en 1977 y veían su trabajo como parte de una conversación diaspórica sobre arte, raza y colonialismo. En su manifiesto fundacional (1978) lo dijeron claramente: "Las Antillas es nuestro medio afín, real... no nos interesan otros mundos." Los artistas de Grupo Antillano veían su trabajo como parte de una larga tradición de lucha, afirmación cultural y resistencia, eso que un médico de Louisiana del siglo XIX había descrito como una enfermedad propia de esclavos: la drapetomanía. Los principales síntomas de esta curiosa enfermedad eran el impulso irresistible a huir y a escapar de la esclavitud.

Esencialmente, estas visiones artísticas dispares apuntan a interpretaciones alternativas de lo que significa ser cubano y lo que constituye una verdadera cultura nacional. En otras palabras, este es un debate acerca de lo que Cuba es y debía ser y de cómo manejar el problema perenne de la diversidad racial del país. Este debate es particularmente intenso en la actualidad, cuando diversos actores sociales y culturales intentan imaginar los futuros posibles de Cuba y el papel que los cubanos de ascendencia africana jugarán en los mismos.

GRUPO ANTILLANO

EXHIBITS/EXPOSICIONES. 1978-1983

1

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Galería Centro de Arte Internacional, 16 de septiembre.

Centro de Arte Internacional Gallery, September 16.

2

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Teatro Mella, espectáculo del Conjunto Folklórico Nacional, 8 de octubre.

Teatro Mella, show of Conjunto Folklórico Nacional, October 8.

3

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Sede del Conjunto Folklórico Nacional, calle 4 y Calzada.

Conjunto Folklórico Nacional Building, calle 4 and Calzada.

4

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

VI Festival Internacional de Ballet, Teatro Mella, 15 de noviembre.

Sixth International Ballet Festival, Teatro Mella, November 15.

5

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Teatro Mella, en temporada de Danza Nacional de Cuba, 20 de noviembre.

Teatro Mella, during season of Danza Nacional de Cuba, November 20.

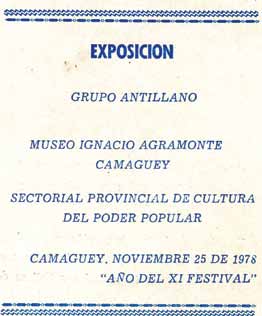

6

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Museo Ignacio Agramonte, Camagüey, 25 de noviembre.

Ignacio Agramonte Museum, Camagüey, November 25.

7

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

CUBATUR, La Rampa, 27 de diciembre.

CUBATUR building, La Rampa, December 27.

8

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Teatro Guiñol, para la función de “Shangó de Ima”, 30 de diciembre.

Teatro Guiñol, for staging of “Shangó de Ima”, December 30.

GRUPO ANTILLANO

El arte y literatura es la más sutil y profunda representación de los pueblos es y su medio social y desarrollo.

En estas manifestaciones proyectan a plenitud su personalidad y reafirman su nacionalidad. El imperialismo es conocedor de este fenómeno, por ello su incesante lucha por penetrar culturalmente a los pueblos, teniendo como objetivo básico el logro de su despersonalización y desnacionalización.

El pueblo cubano no podía escapar a este fenómeno de lucha ideológica; así en la década del 30 paralelo a la Revolución que se gestaba, se producía un movimiento cultural de raíces genuinamente cubanas con el cual se iniciaba el encuentro y desarrollo de nuestra personalidad y con ella, la reafirmación de nuestra nacionalidad y razón de ser.

Una vez más en nuestra historia fue arrebatada por el imperio nuestra revolución, frenando, retrotrayendo y pretendiendo degenerar nuestro medio. A esta pretensión material socio-económica del imperialismo no podía escapar el fenómeno espiritual cuya fuerza y poder conocen y, comienza la penetración cultural, deformando y desviando el movimiento cuyo inicio, no por casualidad, coincidía con aquel frenado proceso.

La penetración jamás logró su objetivo, fuerzas indomables por su legítima representación del pueblo, quedaban dando su gran batalla ideológica, este es el caso entre otros de Nicolás Guillén.

Este movimiento consciente o inconscientemente asentaba todas las inquietudes y razón de ser en los orígenes étnicos de nosotros los cubanos “nuestro perfil definitivo”. “Somos latino-africanos” dijo nuestro comandante en jefe, definiendo así profundamente las raíces de nuestro mundo y el único camino posible para el desarrollo de nuestra personalidad y conciencia nacional, lo que se dio en llamar en música el afro-cubano y, lo que consideramos que simplemente podemos sintetizar designándolo como cubano. Cubano que es la resultante de nuestros orígenes latino- africano.

En la década del 40 tres pintores aisladamente y aún sin conocerse, comienzan a transitar por este camino marcado por Guillén y Roldán, entre otros, y hoy definido por nuestro máximo jefe. La lucha no les fue fácil, los prejuicios sociales, raciales, etc. que no podían asimilar la veracidad y plenitud de nuestro mestizaje, los combatía pese a la fuerza y calidad de su obra.

Hoy al triunfo definitivo de nuestra revolución y tomando ésta el carácter socialista que la define y orienta, se han liberado las fuerzas creadoras reprimidas en nuestro pueblo y, observamos cómo al igual que ayer limitadamente por la represión cultural existente entonces, se manifiestan en mayor número, distantes entre sí, sin conocerse en el orden personal e incluso, sin conocer mutuamente la obra de cada cual en sus pasos iniciales, un grupo de pintores y escultores cubanos que motivados simplemente por su profunda condición de cubanos, por la sensibilidad que les viene dada por sus orígenes étnicos, toman consciente o inconscientemente el único camino que les es posible para identificarse a sí mismo.

No es la creación de un grupo que alza un nuevo concepto para luchar por él, no, es el reagrupamiento de un grupo de artistas plásticos que hace años vienen transitando por este camino, algunos hace 35 años, otros 15; así con el único acicate de su plenitud, y hoy identificados entre sí, vinculándose con lo que les es más afín para analizar en conjunto el camino que aisladamente, hasta aquí, han recorrido y que en nuestra conciencia es el único capaz de dar razón de ser, el que nos vincula a nuestros orígenes y cuyo ulterior desarrollo nos habrá de conducir a nuestro encuentro a una nueva, joven y fuerte cultura y que sólo podríamos designar como Cubana.

Las Antillas es nuestro medio afín, real y, aspiramos una mayor comunicación con nuestros hermanos pueblos de este mundo antillano, no nos interesan otros mundos cuyo entendimiento no puede poseer la profundidad espiritual, no quiere decir que lo rechacemos, no, necesitamos arraigarnos en nuestro lenguaje, fortalecernos conceptualmente, sensitivamente, es lo nuestro lo más inmediato, las Antillas.

Desafortunadamente en esta reagrupación no se encuentran todos los valores afines a estos principios, no es culpa nuestra, les hemos llamado a analizar y conjugar en conjunto haciendo toma de conciencia plena de nuestro camino, ellos cumplen la voluntad de su aislamiento, no les criticamos, sencillamente lo manifestamos, dejando constancia pública, de que no hemos ignorado a nadie, que no es un grupo guiado por intereses personales, que todo él es afín al concepto expuesto, debe de colaborar a hallar nuestro camino plástico y que si algún compañero se nos ha olvidado es por falta de conocimiento nuestro de su personalidad y nos ayudan informándonos.

Nuestro camino no es estético, sin que eludamos la estética, por el contrario, la luchamos como una aseveración de nuestra personalidad, pero la base de nuestro camino en síntesis es lo Cubano.

La Habana, 26 de julio de 1978

GRUPO ANTILLANO

Art and literature are the most refined and pro- found representations of the social condition and development of a people.

Through such manifestations cultural groups project their personality fully and reaffirm their nationality. Imperialism understands this phenomenon, which accounts for its incessant efforts to culturally penetrate other peoples, with the ultimate goal of depersonalization and denationalization.

The Cuban people could not escape this ideological struggle. Thus in the 1930s, parallel with the Revolution then in gestation, a cultural movement emerged with genuinely Cuban roots which began to discover and develop our personality and to reaffirm our nationality and its underlying rationale.

Once again in our history the empire tried to take over our revolution, halting, rolling back, and attempting to chip away at the process. Imperialism understands the strength and power of the spirit, and spiritual phenomena could not escape these material and socio-economic efforts by the forces of imperialism. A process of cultural penetration that deformed and misdirected the movement began, not coincidentally, with the halting steps toward revolution.

Such penetration never achieved its goal. Forces which were indomitable, because they were the legitimate representation of the people, engaged in a great ideological battle. This was the case, among others, of Nicolás Guillén.

Consciously or unconsciously, this movement resolved all the anxieties over the underlying rationale of the ethnic origins of the Cuban people, “our definitive profile.” “We are Latin-Africans,” said our commander in chief, thus profoundly defining the roots of our world and the only possible path for the development of our national personality and consciousness. In music this came to be called Afro-Cuban, and upon reflection we can synthesize it more simply by calling it Cuban. Being Cuban is the result of our Latin-African origins.

In the 1940s three painters, independently and without yet knowing one other began to move along the path marked by Guillén and Roldán, among others, and today defined by our maximum leader. Their struggle was not easy. They were op- posed by social, racial, and other prejudices which could not adjust to the truth and fullness of our mixed blood, despite the strength and quality of their work.

Today, with the definitive triumph of our revolution, and the socialist character that gives it definition and orientation, the repressed creative forces of our people have been liberated. In the past expression was limited by the cultural repression of the times. Today, in contrast, we see a growing number of Cuban painters and sculptors who are motivated simply by their profound condition as Cubans and an awareness of their ethnic origins who consciously or unconsciously are taking the only path possible toward a common identity. When this movement began they were separated by distance, often did not know one another on a personal basis, and even without knowing one another’s work.

This is not the creation of a group that holds forth a new ideal to struggle toward. It is, rather, the reformation of a group of artists who for years have been traveling along this path—some for 35 years, others for 15. Now we have identified ourselves and are connected by the common incentive to analyze together the path that up to now we have traveled separately, which we know to be the only way capable of providing a common rationale which connects us to our origins and whose full development will lead us to our encounter with a new, young, and strong culture which we can only describe as Cuban.

The Antilles are our common real environment, and we aspire to greater communication with our sibling peoples of the Antillean world. We are not interested in other worlds whose understanding cannot have spiritual depth. This does not mean that we reject them, but we need to base ourselves in our own language and strengthen ourselves conceptually and with sensitivity on what for us is most immediately ours—the Antilles.

Unfortunately in this regrouping not everyone finds their values in line with these principles. This is not our fault. We have invited them to analyze and come together while developing full awareness of our path. They are fulfilling their desire for isolation. By saying this we do not criticize them. We simply want to declare publicly that we have not ignored anyone and that this is not a group organized around personal interests. The whole group is united around the ideals expressed here and must collaborate in seeking our artistic path. If we have left out any comrade it is because we do not know him personally, and we would appreciate being so informed.

Although we do not avoid aesthetics, our objective is not simply aesthetic. On the contrary, we struggle toward our objective as a statement of our personality, but the basis of our path is, in sum, what is Cuban.

Havana, 26 of July 1978

9

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Galería Plaza de la Catedral, 17 de enero.

Plaza de la Catedral Gallery, January 17.

10

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Homenaje a Don Fernando Ortiz. Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba “José Martí,” 13 de abril.

Homage to Don Fernando Ortiz. Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba “José Martí,” April 13.

11

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

CARIFESTA, Galería Amelia Peláez, Parque Lenin, 4 de julio.

CARIFESTA, Amelia Peláez Gallery, Parque Lenin, July 4.

12

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

CARIFESTA, Liceo de la Habana Vieja, 9 de julio.

CARIFESTA, Liceo de la Habana Vieja, July 9.

13

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

XX Aniversario de Danza Nacional de Cuba, Taller de Cerámica, Parque Lenin, 13 de septiembre.

Twentieth Anniversary of Danza Nacional de Cuba, Taller de Cerámica, Parque Lenin, September 13..

EN LA HABANA, FIESTA DE LAS ANTILLAS

En el Irisado de oro y azul, verde plumaje de pavo real, y en las delicadísimas panojas azullila de la flor del agua, señorea el ojo custodio de la vida en los trópicos, sus formas y colores esenciales. Ojo solar que en el agua viva se refracta y prolífera para reproducir una de las constelaciones del cielo austral.

No es la blancura implacable del loto, sino el azul de mar y cielo que ciñe y techa el agreste verde insular; es la luz lila, luz impresionista de la zona tórrida; es el amarillo inocente de fruta que madura lento; es el añil purpúreo, el dorado febril y demencial que no pintó Picasso, que no vieron los ojos alucinados de Gaugin.

Abierta cola de pavo real, arco, abanico, fulgurante estela de cocuyos y peces voladores; son Las Antillas que deslumbran los ojos del descubridor y azuzan la codicia y la usura de los conquistadores. Tras el súbito azoro provocado por la vertiginosa exuberancia de las tierras de los Araucos, Caribes y Ciboneyes, se lanzan a la voraz búsqueda de oro.

Tierras ultrajadas, saqueadas; razas martirizadas hasta su exterminio total. Bajo las raíces del bosque y su hojarasca; a la sombra amarillo escarlata del árbol fuego; del verdor copioso del árbol lluvia y del evangélico árbol pan; bajo el minucioso rastreo del majá, de la iguana y la jutía, y el vuelo polícromo de pájaros e insectos, yacen sepultos cenizas y huesos aborígenes.

Es el marrón, el pardo negruzco, el gris metálico, el tinte azafranado y sus evanescentes derivaciones hasta alcanzar el almendrado seminal, germinativo: colores de nuestros suelos, por siglos vandálicamente explotados en cultivos que empobrecían su naturales condiciones y a los hombres que los trabajan.

De la Europa cristiana vino el conquistador y en desfile la cruz, el trabajo forzado, antiguas epidemias, la tortura y la muerte; mercedó tierras y tomó en encomienda al legítimo dueño de estas islas.

Esclavizado pueblo de inocentes manos, adiestradas en procurarse alimento y precario vestidos.

Tienen ellos por cierto que la tierra como el sol, y el agua, es común, y no debe haber entre ellos mío y tuyo.

Pobre, sencillo, humilde pueblo, recurre a rebelarse o al suicidio.

¿Qué reminiscencias de amor por la belleza decora tus vasijas, artefactos rituales? ¿Qué oráculo cobarde te ocultó el fin de la sangre, de grito y sangre, de silencio y sangre? ¿Dónde encontrar tus huellas? ¿Acaso en las azules y grises espirales del humo del tabaco? ¿Acaso en nuestras manos en ronda, en el compás unánime de nuestros pies y voces? ¿En el cemí, en el dujo, en la cojaba?

No es la glacial albura del albatros; es el punzó de la sangre a chorros; el escarlata del ibis antillano; la piel sanguínea del almácigo; la arcilla colorada; el purpura anaranjado de amaneceres y ponientes; el bermellón, el amaranto, el carmesí de flores y plumajes; el firme coralino del subsuelo.

De las costas de Oro y de Marfil, de Guinea y el Congo, de Dahomey y Nigeria, de Loango y Angola; bordeando el cabo de Buena Esperanza hacia el este hasta Mozambique, arracimado en montón, entre cadenas, excremento, orina; expuestos a la lluvia y al sol feroces del océano, los que salvaron hueso y carne vivos son arrojados al mercado esclavo en las Antillas. Los que salvaron sangre y piel han de darlas al látigo, al cepo, al “bocabajo”, a la sal y al vinagre en las heridas que se ulceran y gangrenan. Los que salvaron corazón y mente por cólera o amor, por odio o fe, sufrirán el ultraje y la ignominia.

Las Antillas hambrientas, las Antillas perladas de viruelas, las Antillas dinamitadas de alcohol varadas en el fango…

Tres siglos que avergüenzan, pero el amo, el señor, no se avergüenza. Hay que esperar a que su sangre amancebada con negra esclava o libre, o fiel a la pureza del linaje se renueve en hijos que reclamen o exijan el sitio principal en sus tierras de origen.

Ya que nacer es aquí una fiesta innombrable.

Hay que esperar a que la flora y la fauna endémicas, los rumores del agua y la tierra, la brisa que baja de los montes hasta la playa, invadan el inocente sueño del recién nacido.

Que cese de dormir cuanto haya de inflamable ¡y ordene nuestros gestos!

¿Quién que se busque perderá sus días sin encontrar el cauce de su sangre; la voz de sus entrañas, su inquebrantable hueso? La lucha ha sido larga, muy larga, demasiado larga. ¿Dónde se inicia el grito libertorio? ¿Es en el Bois Caïman? ¿O en la fuga hacia el monte Cimarrón, su muerte en soledad, su muerte libre? ¿O antes, mucho antes cuando el aborigen se enfrenta y lucha contra el conquistador? Exterminado el hombre de estas islas ¿qué raíces de amor nos fijan a su suelo? ¿Son las lenguas del blanco y sus creencias; las del negro y su fe? ¿Sus mitos y su historia; su miseria y su riqueza? ¿Qué y quiénes somos en tanto que antillanos? Antigua miel y sal también antigua, aguas que se entrecruzan; flor y raíz, alegría y nostalgia, realidad y delirio, inocencia y malicia.

Traemos nuestro rasgo al perfil definitivo de América

¡Eh, compañeros, aquí estamos! Expresamos nuestro ser antillano, lo mostramos limpio como la luz que nos rodea. Aquí están nuestras luchas y victorias, el revés y la gloria. Dioses, guerreros, héroes; la voz oculta del tambor y el clarín que despierta; las escamas del pez y del anón: la majestad de piña y tocoloro; los reinos del Zunzún, del ave flor, de la flor insecto. Somos esto que ven –dicen Manuel Cruceiro, Ramón Haití, Clara Morera, Rogelio R. Cobas, Leones Morales, Rafael Queneditt, Ever Fonseca, Arnaldo R. Larrinaga y Esteban Ayala. ¡Aquí estamos!

Y está aquí y son historia viva: pasado para hacer más humano el presente, más hermoso y alegre el día por venir. De cierto que ellos no andan en busca del ser perdido en las noches del mar y la manigua, de la mina y el surco. No imaginan ni inventan, reproducen la historia, la hacen y viven cada día, a golpes de machete, a tajos como en las guerras y en los cañaverales. A golpes de cincel y martillo, a trazos poderosos y firmes, sin que falten en ellos la antigua flor que el tiempo no deshace, ni la flor en capullo que espera a que amanezca para darnos su aroma y sus colores.

Están aquí y ahora, preparados para iniciar la fiesta de las islas, la fiesta de los mares y del hombre de mar y tierra. ¡La fiesta caribeña!

Están aquí, diciéndonos: Somos dueños de una tan rica heredad en etnias y diversa en culturas sincréticas, tan poderosa y firme en rebeldía, tan determinados a ser libres e iguales. Somos los herederos y continuadores de la obra de Louverture, Bolívar, Juárez, Martí y Garvey.

¡Compañeros no es la sequía perpetua nuestra herencia!

Pues, Nuestra sonrisa madrugará sobre los ríos y los pájaros

Pablo Armando Fernández (1979)

In Havana, Festival Of The Antilles

In the iridescent gold and blue green plumage of the peacock, and the most delicate blue-lilac flower clusters of the water lily, the eye that cares for life in the tropics, with its essential shapes and colors, holds sway.

The eye of the sun that refracts and proliferates in the lively water to reproduce one of the constellations of the southern sky.

It is not the implacable whiteness of the lotus, but the blue of the sea and sky that surrounds and covers the

rustic island green. It is the purple light, the impressionistic light of the torrid zone. It is the innocent

yellow of fruit that ripens slowly. It is the indigo purple, the demented and feverish golden tone that Picasso did not paint, that Gauguin’s wild eyes did not see The open tail of the peacock, rainbow, fan, resplendent

frieze of fireflies and flying fish; these are the Antilles that dazzle the eyes of the discoverer and incite the greed and profit of the conquistadors.

After the sudden bewilderment provoked by the giddy exuberance of the land of the Arawaks, Caribs, and Ciboneyes, they threw themselves into the voracious quest for gold.

Lands raped and pillaged, races martyred to the point of total extermination. Under the roots and matted floor of the forest, in the yellow scarlet shade of the fire tree, of the copious greenery of the rain tree and the evangelical bread tree, under the precise tracks of the majá snake, the iguana, and the jutía, the multi-colored flight of birds and insects, the ashes and bones of aboriginal peoples lie buried.

It is brown, a blackish brown, metallic grey, a saffron tint and its evanescent derivations up to a seminal, germinal almond tone—the colors of our soils which for centuries have been exploited by crops that impoverished its natural condition and the men who work in it.

From Christian Europe came the conquistador and in his train the cross, forced labor, old epidemics, torture, and death. He granted lands and took the legitimate owners of these islands into his domain.

An enslaved people with innocent hands, adept at finding food and minimal clothing.

They believe for certain that the land, like the sun and the water, is common to all, and that among them there should be no mine and yours.

Poor, simple, humble people, prone to rebellion or suicide.

What recollections of the love of beauty decorate your pots, ritual artifacts? What cowardly oracle hides from you the purpose of blood, screams and blood, silence and blood? Where does one find traces of him? Perhaps in the blue and grey spirals of tobacco smoke? By chance in our hands in a circle? In the unanimous beating of our feet and voices? In the cemí [Taino spirit], in the dujo [Taino chair], in the cojaba tree?

It is not the glacial whiteness of the albatross. It is the dark red of gushing blood, the scarlet of the Antillean ibis, the blood-like bark of the mastic tree, red clay, the purple orange of sunrises and sunsets, vermillion, amaranth, crimson flowers and feathers, the hard coral from underground. From the gold coast and the ivory coast, from Guinea, the Congo, Dahomey and Nigeria, from Loango and Angola, from the Cape of Good Hope east to Mozambique, piled in a heap, mixed in with chains, excrement, urine, exposed to the fierce rain and sun of the ocean. Those who survived as bone and flesh are thrown into the slave markets of the Antilles. Those who survived as blood and skin have to be subjected to the whip, the stocks, being tied face down, salt and vinegar in infected and gangrenous wounds. Those who survive with heart and mind will suffer rape and disgrace, out of rage or love, hate or faith.

The hungry Antilles, the Antilles pitted with smallpox, the Antilles dynamited by alcohol, stranded in the mud . . .

Three centuries of shame, but the master, the lord, is not ashamed. It is necessary to wait until his blood is mixed with that of the black concubine, slave or free, or true to the purity of the lineage is passed on to children who claim or demand the big house of the lands on which they were born. Because to be born here is an unnamable fiesta.

One must wait for the endemic flora and fauna, the murmurs of the water and earth, the breeze that comes down from the hills to the beach, to invade the innocent sleep of the newborn baby.

Anything flammable should cease to sleep, and let it organize our next steps!

Will those who go looking for themselves waste their time without finding the channel of their blood, the voice of their heart, their unbreakable bone? It has been a long struggle. Very long. Too long. Where does the cry of freedom begin? In the Bois Caïman? Or in the escape to the cimarrón mountains, the lonely death, the free death? Or earlier, much earlier when the indigenous people confront and struggle against the conquistador?

With the native people of these islands exterminated, what roots of love attach us to their soil? Are they the languages and beliefs of the whites? The blacks and their faith? Their myths and their history, their poverty and wealth? What and who are we as Antillean people? Old honey and salt that is also old, waters that blend with themselves, flower and root, joy and nostalgia, reality and delusion, innocence and malice.

We bring our traits to the definitive profile of America

So, comrades, here we are! We express our Antillean identity, we show it as clean as the light around us. Here are our battles and victories, the reverses and the glories. Gods, warriors, heroes; the hidden voice of the drum and the awakening bugle; the scales of the fish and of the custard apple tree; the majesty of the pineapple and the Cuban trogon; the kingdoms of the hummingbird, of the bird of paradise flower, the insect flower. We are what you see. As Manuel Couceiro, Ramón Haití, Clara Morera, Rogelio R. Cobas, Leonel Morales, Rafael Queneditt, Ever Fonseca, Arnaldo R. Larrinaga and Esteban Ayala all say: Here we are!

Here and living history: the past to make the present more human, and the future more beautiful and joyful. Of course they do not wander in search of the being lost in the sea at night, in the jungle, the mine, or the field. They do not imagine nor invent. They reproduce history, make it, and live it every day, by machete blows, slashing as in battle and in the cane fields. With blows of the hammer and chisel, powerful and firm strokes. But they still have in them the old flower that time does not diminish, and the budding flower that waits for the morning to give us its scent and its colors.

They are here and now, ready to begin the fiesta of the islands, the fiesta of the seas and of the man of sea and land. The Caribbean fiesta!

They are here and saying to us: We are the heirs of a rich ethnic legacy of diverse and syncretic cultures, so powerful and firm in rebellion, so determined to be free and equal. We are the heirs and successors of the work of L’Ouverture, Bolívar, Juárez, Martí, and Garvey.

Comrades our legacy is not perpetual drought!

Because, Our smile will break the dawn over the rivers and birds.

Pablo Armando Fernández (1979)

14

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Casa de la Cultura Cubana en Praga, Checoslovaquia, enero.

Casa de la Cultura Cubana in Prague, Czechoslovakia, January.

15

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Seminario “Veinte Años de Independencia Política en África” del Centro de Estudios de África y Medio Oriente, Academia de Ciencia de Cuba, 21 de mayo.

Seminar “Twenty Years of Political Independence in Africa,” Centro de Estudios de África y Medio Oriente, Academia de Ciencia de Cuba, May 21.

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Ciclo de Conferencias organizado por el Grupo. “Algunos aspectos que han incidido en el desarrollo de la nacionalidad cubana”, Salón Rubén Martínez Villena, UNEAC, julio.

Lecture Series organized by the Group on “Elements that have contributed to the formation

of the Cuban nationality,” Salón Rubén Martínez Villena, UNEAC, July.

16

17

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Galería del Comité de la Cultura, Sofía, Bulgaria, 30 de julio.

Comité de la Cultura Gallery, Sofia, Bulgaria, July 30.

19

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Homenaje al Centenario de Don Fernando Ortiz, Galería Habana, julio.

Homage Centennial of Don Fernando Ortiz, Habana Gallery, July.

20

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

CARIFESTA 81, Community College, Barbados, 15 de julio.

CARIFESTA 81, Barbados Community College, July 15.

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Buque “XX Aniversario,” puertos de Barbados y Curazao, julio-agosto.

Ship “XX Aniversario,” ports of Barbados and Curacao, July-August.

21

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Teatro Mella, julio-diciembre.

Teatro Mella, July-December.

22

23

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Sala Covarrubias, Teatro Nacional, octubre.

Sala Covarrubias, Teatro Nacional, October.

Don Fernando Ortiz, el centenario de cuyo natalicio se conmemora el presente año, supo descubrir para sus contemporáneos y para la posteridad el aporte de los pueblos africanos a la formación del pueblo cubano, de nuestra cultura nacional.

Su gran mérito consistió en que su magna obra tuvo lugar en el seno de una sociedad en que las clases dominantes imponían el racismo y la discriminación, en que se negaban tales aportes. Por ello, lejos de ser creación estrictamente erudita, la obra de Ortiz tuvo proyecciones de lucha contra la discriminación y el racismo, por la reafirmación de la identidad nacional formada a partir de raíces hispánicas y africanas, en singular proceso de transculturación.

Los aportes africanos a la cultura cubana, la transculturación afrohispánica, sirvieron de inspiración, en aquella sociedad hostil al negro, a creadores en distintos campos que son orgullo de nuestro pueblo. Entre ellos cabe mencionar a Nicolás Guillén, Wifredo Lam, Alejo Carpentier, Amadeo Roldán, que han sido expositores geniales de nuestra cultura nacional.

En contraste con la sociedad del pasado, esencialmente discriminatoria, la Revolución Socialista de los humildes y para los humildes en el poder, ha hecho posible la proclamación por el Comandante en Jefe Fidel Castro del carácter latino-africano de nuestro pueblo. Con la existencia de una cultura socialista, que incorpora definitivamente a nuestro patrimonio nacional los valores presente en la cultura popular, los valores representados por nuestras raíces africanas pasan a engrosar este caudal.

La obra creadora del Grupo Antillano se inscribe en este contexto, incorporando formas, texturas y matices provenientes de nuestros ancestros africanos pero que son hoy patrimonio que pertenece a todo nuestro pueblo.

Rafael L. López Valdés, 1981

Sin que aún se haya cumplido el primer aniversario de la exposición inaugural, que abriera sus puertas –para alegría de la cultura cubana y caribeña- en la Galería Centro de Arte Internacional de La Habana en septiembre de 1978, el joven Grupo Antillano puede sentirse satisfecho de contar en su haber una vibrante vida creadora, plasmada en más de cinco exposiciones y en actividades didácticas ofrecidas en centros de trabajos.

Hoy, de nuevo, nos brinda los frutos recientes de su continua exploración por los umbrosos maniguales de nuestro mundo isleño, bañado por el apacible o borrascoso Caribe, y una vez más estalla en sus obras toda la riqueza formal y temática de nuestras tradiciones populares, asimiladas y recreadas con una sensibilidad contemporánea por Manuel Coucerio, Ramón Haití, Leonel Morales, Rafael Queneditt, Rogelio R Cobas, Arnaldo Larrinaga, Ever Fonseca, Esteban Ayala y Clara Morera –la más reciente adquisición del Grupo. En las pinturas, dibujos, grabados, esculturas, cerámicas, diseños gráficos y ensamblajes de estos plásticos –cubanos raigales-, la tradición se expande y revitaliza; un arte nuevo hace oír su voz, su esencia y presencia, nutriéndose de algunas de las más ricas torrenteras del patrimonio que nos legaron nuestros antepasados, explayando también una euforia existencial que sólo conocen los pueblos liberados definitivamente.

Las formas animales o vegetales, los símbolos y atributos mitológicos, la exuberancia de los cuerpos crecidos bajo la luz caribeña, los colores pastosos y estallantes, las fosforescencias marinas y nocturnas, el ritmo, la elegancia, las suculentas texturas y sus pátinas; en fin, la alegría experimentada frente a todas y cada una de las obras expuestas por este grupo de creadores, nos impulsan a saludarlo con la fórmula tradicional y sonora heredada de los antiguos yorubá: ¡Kawo Kabiesile! (¡Larga vida a vosotros, hijos de las Antillas!).

Rogelio Martínez Furé, 1979

Don Fernando Ortiz, the centenary of whose birth is being commemorated this year, was able to discover for his contemporaries and for posterity the contribution of African peoples to the development of the Cuban people, to our national culture.

His great accomplishment was that his great work was carried out in the midst of a society in which the dominant classes imposed racism and discrimination, and denied those contributions. Thus, rather than being strictly scholarly material, Ortiz’s work was projected into the struggle against discrimination and racism, through the reaffirmation that our national identity was shaped by both Spanish and African roots, in a unique process of transculturation.

The African contributions to Cuban culture, and Afro-Hispanic transculturation, served as inspiration, in that society hostile to blacks, to creative people in several fields who are the pride of our people. Among them we should mention Nicolás Guillén, Wifredo Lam, Alejo Carpentier, and Amadeo Roldán, who have been ingenious exponents of our national culture.

In contrast to the society of the past, which was essentially discriminatory, the Socialist Revolution of the humble and for the humble in power, has made possible the proclamation by the commander in chief Fidel Castro that we are a Latin-African people. With the existence of a socialist culture that definitively includes in our national patrimony the values present in the culture of the people, the values represented by our African roots have entered the mainstream.

The creative work of Grupo Antillano falls within this context, incorporating shapes, textures, and shadings derived from our African ancestors but which are now the patrimony of all our people.

Rafael L. López Valdés, 1981

For all Cuban artists who want to know deeply their historical and cultural roots, for anyone who aspires to drink deeply of the traditional and book-based wisdom accumulated by their ancestors, the work of Don Fernando is required reading, the point of departure, the compass orientation to renewed encounters. The Grupo Antillano, faithful to the profound Cubanness of our wise writer, exalts him in every one of its artistic creations, delves into the magical realism of the lives of our people, and strives to the truly free conquest of renovating forms. Tradition is exalted as nourishing wisdom but it never becomes the prison of the imagination.

The artist chooses, recreates, and establishes realities according to his sensitivity as a modern man. He drinks in the ancestral fountains, but bravely throws himself into the conquest of new states of Cubanness, with the eternal cimarrón spirit of our Antillean world.

Rogelio Martínez Furé, 1981

34

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

V Aniversario del Grupo Antillano en Homenaje a Wifredo Lam en el primer

aniversario de su deceso, Galería Plaza Vieja, septiembre.

Fifth Anniversary of Grupo Antillano, Homage to Wifredo Lam in the First

Anniversary of His Death, Plaza Vieja Gallery, September.

24

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Festival de Teatro, Teatro Mella, enero.

Festival of Theater, Teatro Mella, January.

25

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

II Festival de las Artes del Caribe, Galería Oriente, Santiago de Cuba, abril.

Second Festival of Caribbean Art, Oriente Gallery, Santiago de Cuba, April.

26

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

XX Aniversario del Conjunto Folklórico Nacional, Teatro Mella, 6 de mayo.

Twentieth Anniversary of Conjunto Folklórico Nacional, Teatro Mella, May 6.

27

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

“América Negra”, Instituto del Tercer Mundo, Ciudad de México.

“Black America,” Instituto del Tercer Mundo, México City.

28

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Homenaje a Sergio Vitier. Sala Avellaneda, Teatro Nacional, 28 de mayo.

Homage to Sergio Vitier. Sala Avellaneda, Teatro Nacional, May

29

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

“Diáspora Africana”, Surinam, 21 de julio.

“African Diaspora,” Suriname, July 21.

30

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

“¡Aquí estamos! Homenaje a Nicolás Guillén,” Galería Amelia Peláez, Parque Lenin, julio.

“Here We Are! Homage to Nicolás Guillén,” Amelia Peláez Gallery, Parque Lenin, July.

31

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

“In Memoriam, Wifredo Lam,” Sala Thalía, Surinam, 6 de diciembre.

“Wifredo Lam in Memoriam,” Thalía Room, Suriname, December 6.

32

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Homenaje a Manuel Couceiro, Galería Amelia Peláez, Parque Lenin, diciembre.

Homage to Manuel Couceiro, Amelia Peláez Gallery, Parque Lenin, December.

33

EXHIBITION / EXPOSICION

Exposición permanente, Casa del Caribe, Santiago de Cuba.

Permanent Exhibit, Casa del Caribe, Santiago de Cuba.