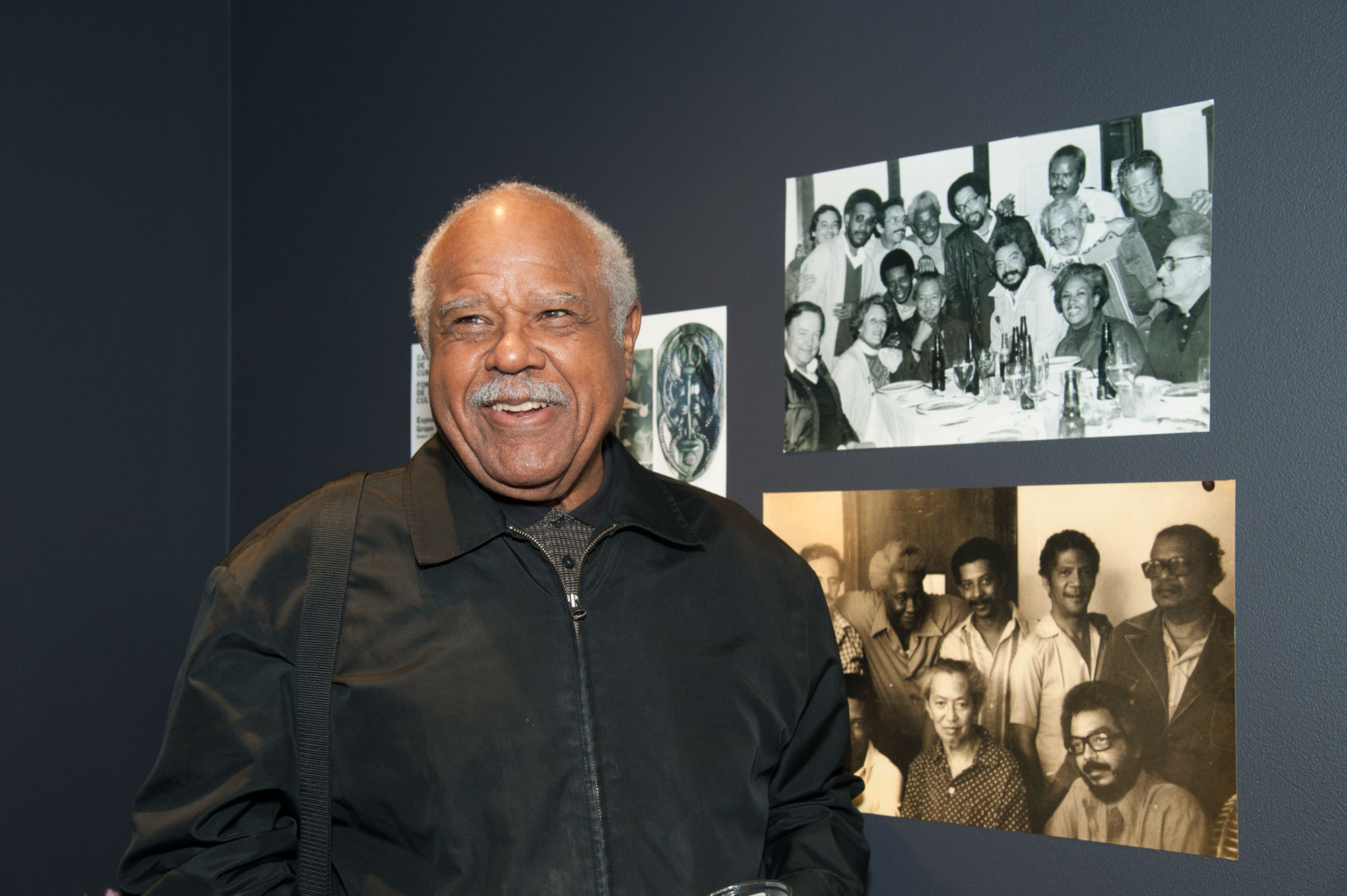

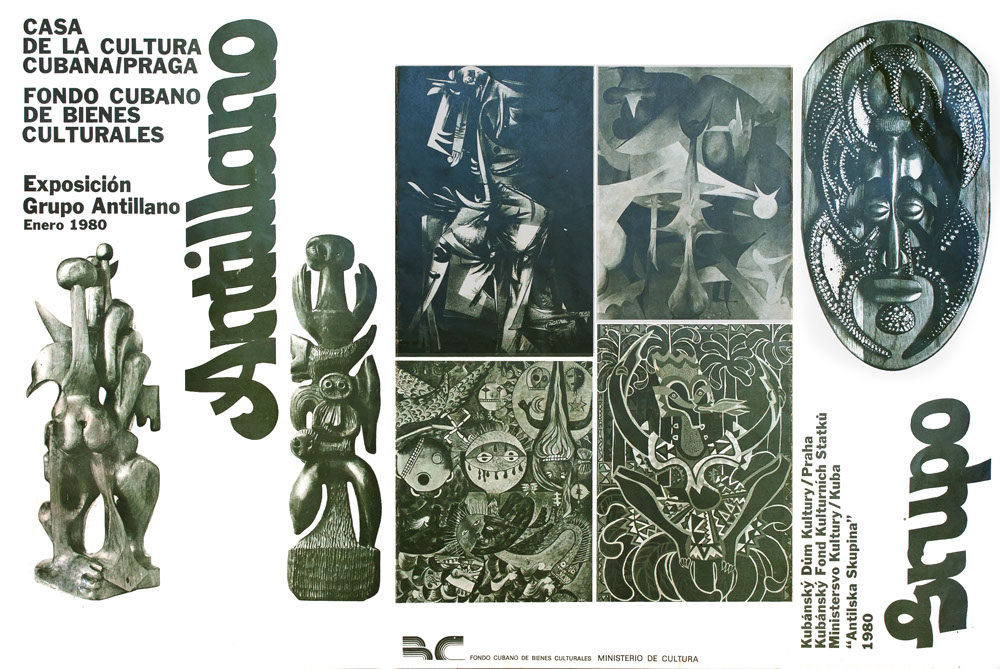

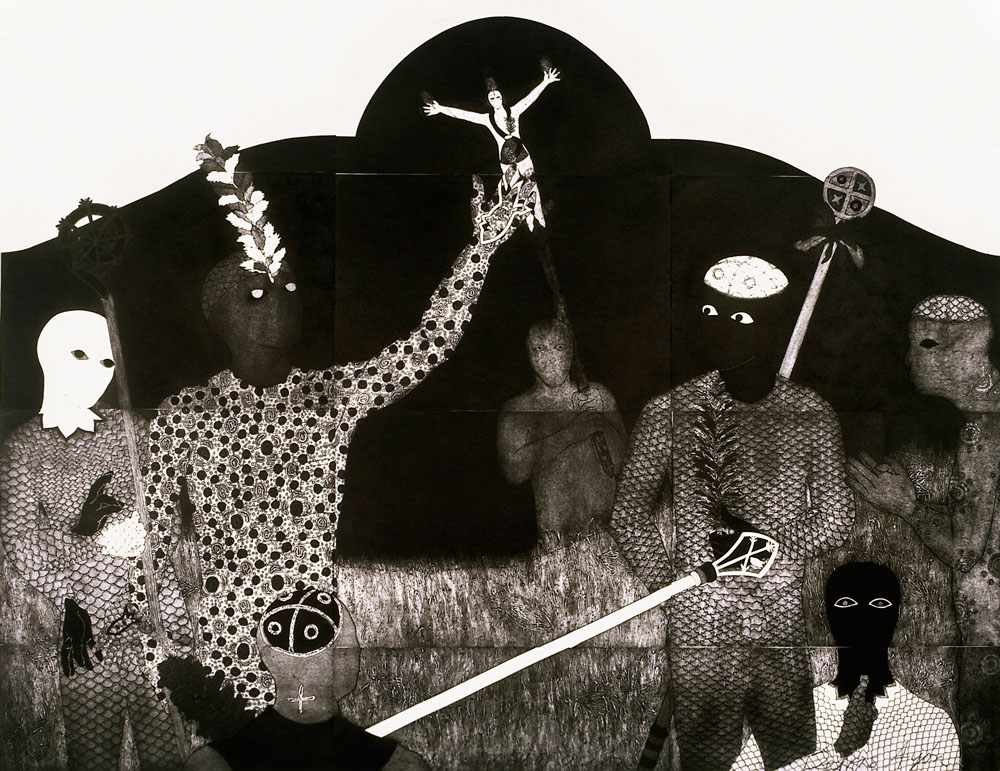

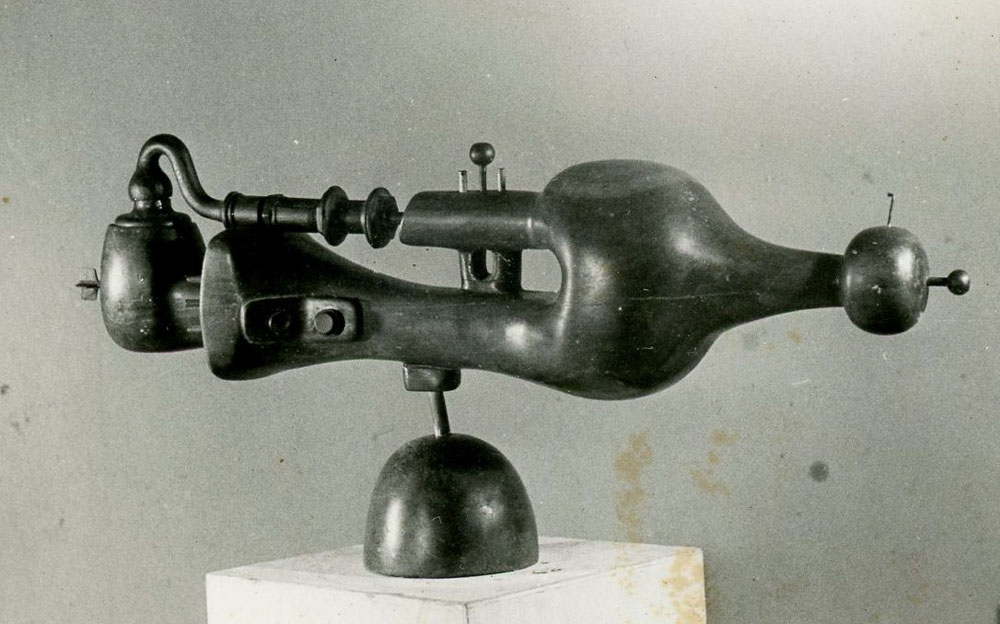

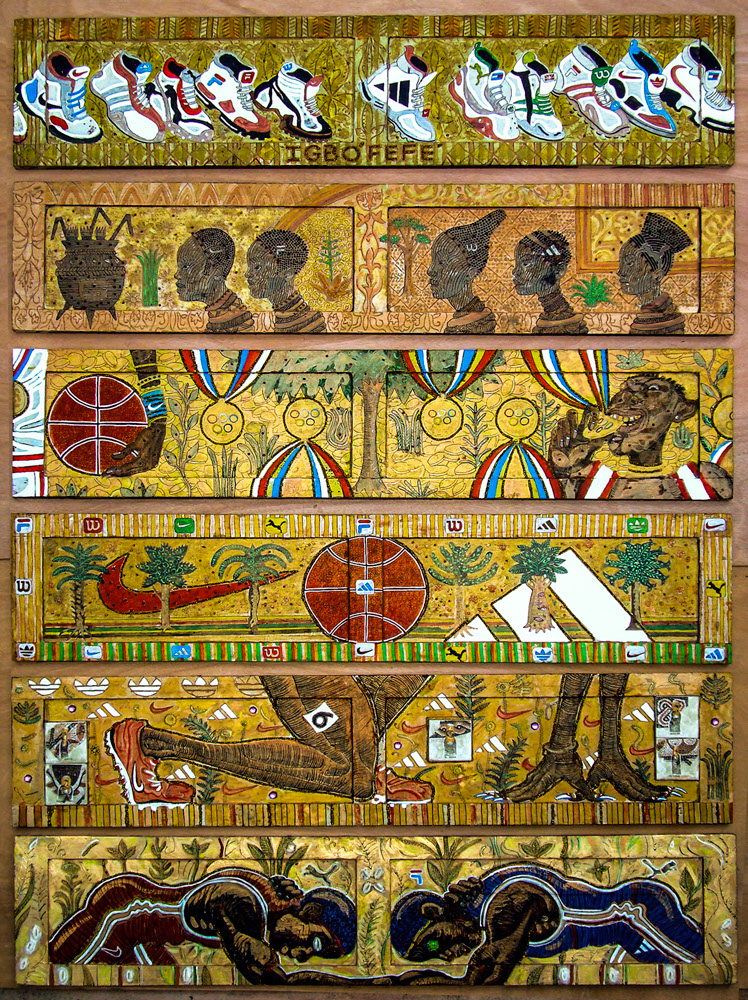

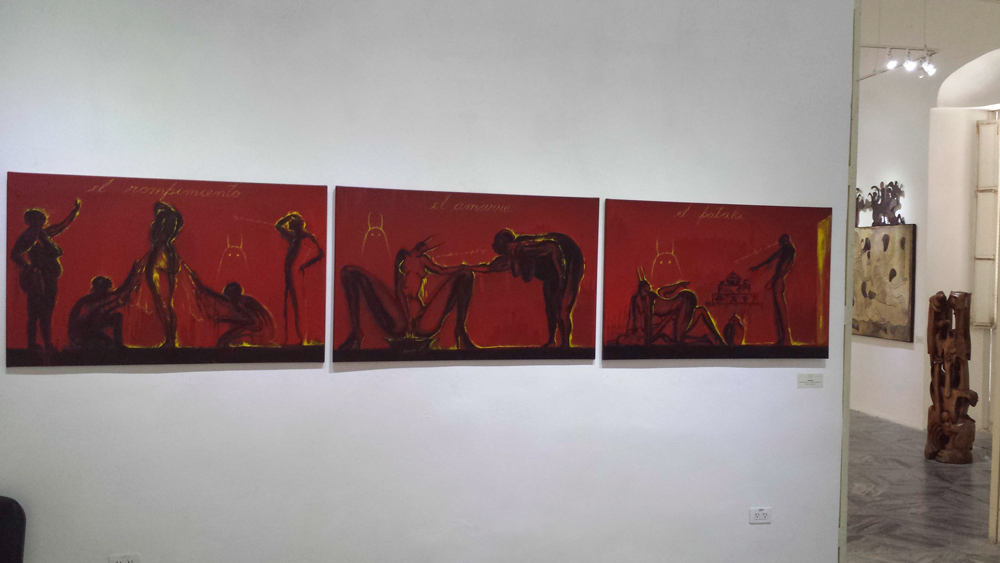

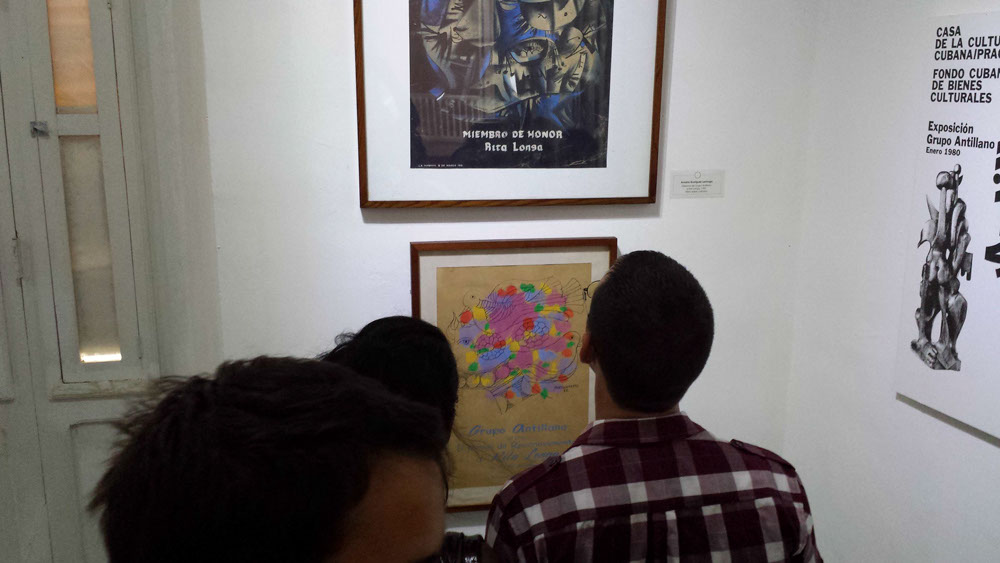

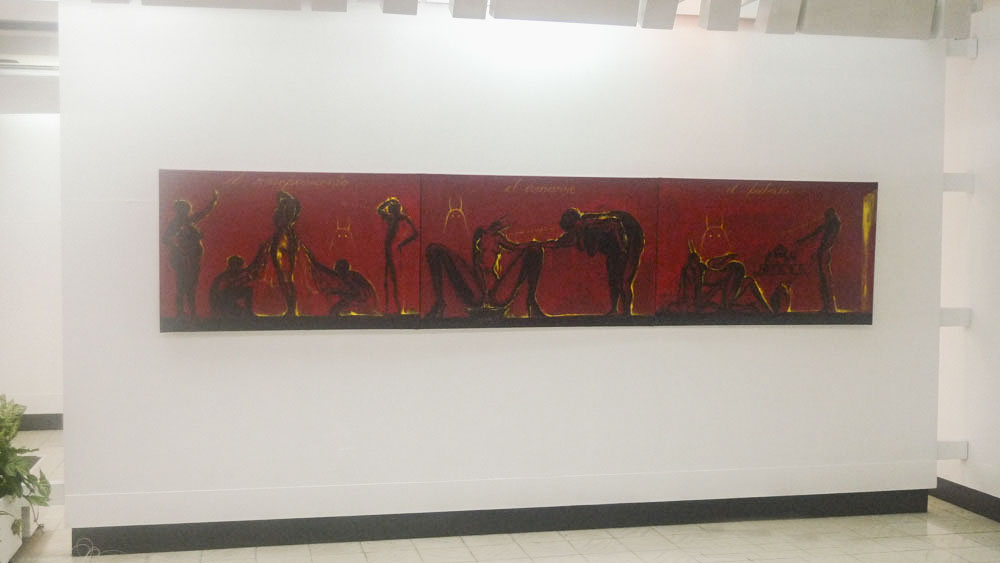

This exhibit is a tribute to Grupo Antillano (1978-1983), a forgotten visual arts and cultural movement that privileged the importance of Africa and Afro-Caribbean influences in the formation of the Cuban nation.

During its five years of existence, Grupo Antillano articulated a new vision of Cuban culture through the visual arts. This vision was popular, radical, Caribbean, Maroon, African, revolutionary. As the founding manifesto of the Group claims, they did not want to promote a new artistic concept, but rather sought to highlight the centrality of Africa in Cuban culture and to debunk dominant narratives that equated Cuban progress and modernity with European influences. They valiantly opposed the persistent belief, supported by vast sectors of the Cuban bureaucracy in the 1970s, that Afro-Cuban religious practices were backward, primitive and grotesque--a "remnant of the past," as they were frequently described at the time. Cuba, Grupo Antillano proclaimed, was quintessentially an Afro-Caribbean nation. Cuban modernity was anchored in the knowledge, the aesthetics, the cultures and the sweat and blood of the African peoples. "We are not interested in other worlds," their foundational manifesto asserted.

The art of Grupo Antillano belongs to a long tradition of Caribbean resistance and cultural assertion. It is part of what Haitian writer René Depestre described as the African slaves' “prodigious effort at legitimate defense” and "ideological cimarronaje" (from "cimarrón" or runaway slave) by which they managed to recreate their pasts and cultures in the new world.

In an article published in the mid-19th century, a medical doctor in a Louisiana plantation described a new disease among slaves. The most visible symptom of this disease, called drapetomania, was an irrepressible and pathological urge to flee and to be free. A form of resistance practiced by African slaves since the beginnings of European colonization in the Americas was transformed into a psychiatric disease, a deviation of the natural order.

It is thanks to the work of a large number of Caribbean intellectuals--like those involved in this exhibit--that what was described by the racist pseudo-science of the 19th century as an expression of disorder became a symbol of rebellion and resistance against European colonial oppression--the foundations of a new order. In the twentieth century, Caribbean thinkers such as Aimé Césaire, René Dépestre, Edward Kamau Brathwaite and Édouard Glissant conceptualized cimarronaje as an expression of cultural resistance and as a central feature of Caribbean identity. It is in this tradition of identity-building and Caribbean assertiveness that the work of Grupo Antillano needs to be analyzed. Founded by sculptor and engraver Rafael Queneditt Morales, Grupo Antillano's foundational manifesto stated clearly that they wanted to recreate the Caribbean and African foundations of an authentic Cuban culture. They also made clear that, to them, Africa was a lively and vital cultural reference, not a dead historical heritage. Fortunately, as Édouard Glissant once stated, the runaway slaves' indomitable resistance is still with us. Fortunately, we have that history, our history, the history that Grupo Antillano tried to reconstruct and to tell.

<

>

Esta exposición rinde homenaje a Grupo Antillano, un movimiento cultural y artístico que entre 1978 y 1983 propuso una visión de la cultura cubana que resaltaba la importancia de los elementos africanos y afro-caribeños en la formación de la nación cubana. En respuesta a los que en los años setenta presentaban la Santería y otras prácticas religiosas y culturales afrocubanas como primitivas y retrógradas, Grupo Antillano destacó valientemente la centralidad de las culturas africanas en cualquier caracterización de la cultura nacional. Para los artistas de Grupo Antillano, África y el Caribe circundante no eran influencias muertas o inertes, sino influencias vitales que continuaban definiendo el ser cubano.

El arte de Grupo Antillano forma parte de una larga tradición caribeña de resistencia y afirmación cultural, de creación de espacios e identidades propios. Es un ejemplo magnífico de ese “prodigioso esfuerzo de legítima defensa” y de “cimarroneria ideológica” que, al decir de René Depestre, permitió a las masas esclavizadas del hemisferio reelaborar sus pasados y culturas.

A mediados del siglo XIX, un médico de esclavos en el sur plantacionista americano, describió una enfermad privativa de esclavos: la drapetomanía. Del griego drapetes (escapar, huir) y manía (locura), el síntoma más visible de esta curiosa enfermedad era la tendencia irrefrenable y patológica de muchos esclavos a huir y a ser libres. Es decir, el galeno describió el cimarronaje como un padecimiento, una enfermedad, una desviación del orden natural, una expresión del indómito salvajismo de los negros.

Es sólo gracias a la creatividad y el ingenio de numerosos intelectuales y artistas caribeños--como los que participan en esta exposición--que hemos logrado transformar la aberración decimonónica en un gesto fundacional. Es gracias al trabajo de pensadores y artistas como los vinculados a Grupo Antillano que hoy podemos celebrar una cubanidad cimarrona y caribeña. Lo que el galeno describió como des/orden se ha convertido en piedra angular de un nuevo orden, de una utopía de espacios e identidades compartidos. Afortunadamente, como dijera el gran poeta martiniqueño Édouard Glissant, “el antiguo cimarronaje de los esclavos... opera nuevamente para nosotros.” Afortunadamente tenemos esa historia, nuestra historia, la historia que Grupo Antillano se ha empeñado en reconstruir y contar.

<

>

<

>

<

>

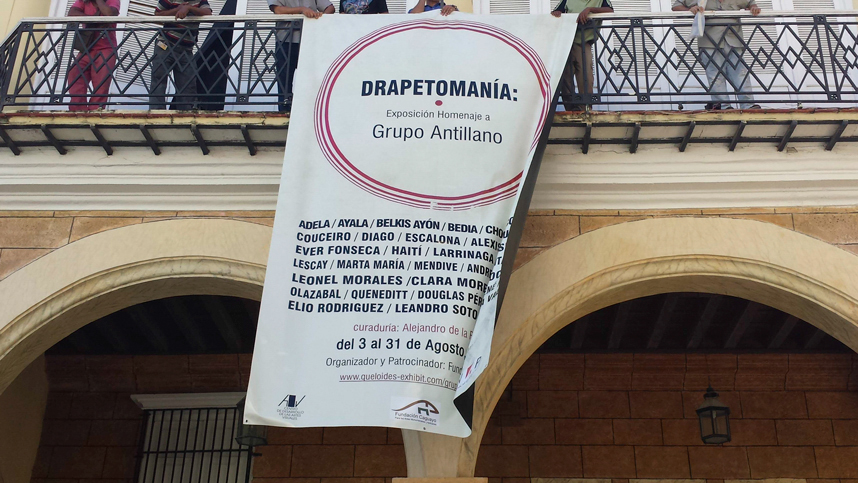

Centro de Desarrollo de las Artes Visuales, Habana, Cuba

3-31 Augst 2013

Cooper Gallery, Harvard University

Cambridge, MA, USA

27th Jan / May 29th 2015

Centro Provincial de Artes Plásticas y Diseño, Santiago de Cuba, Cuba

March-April 2013

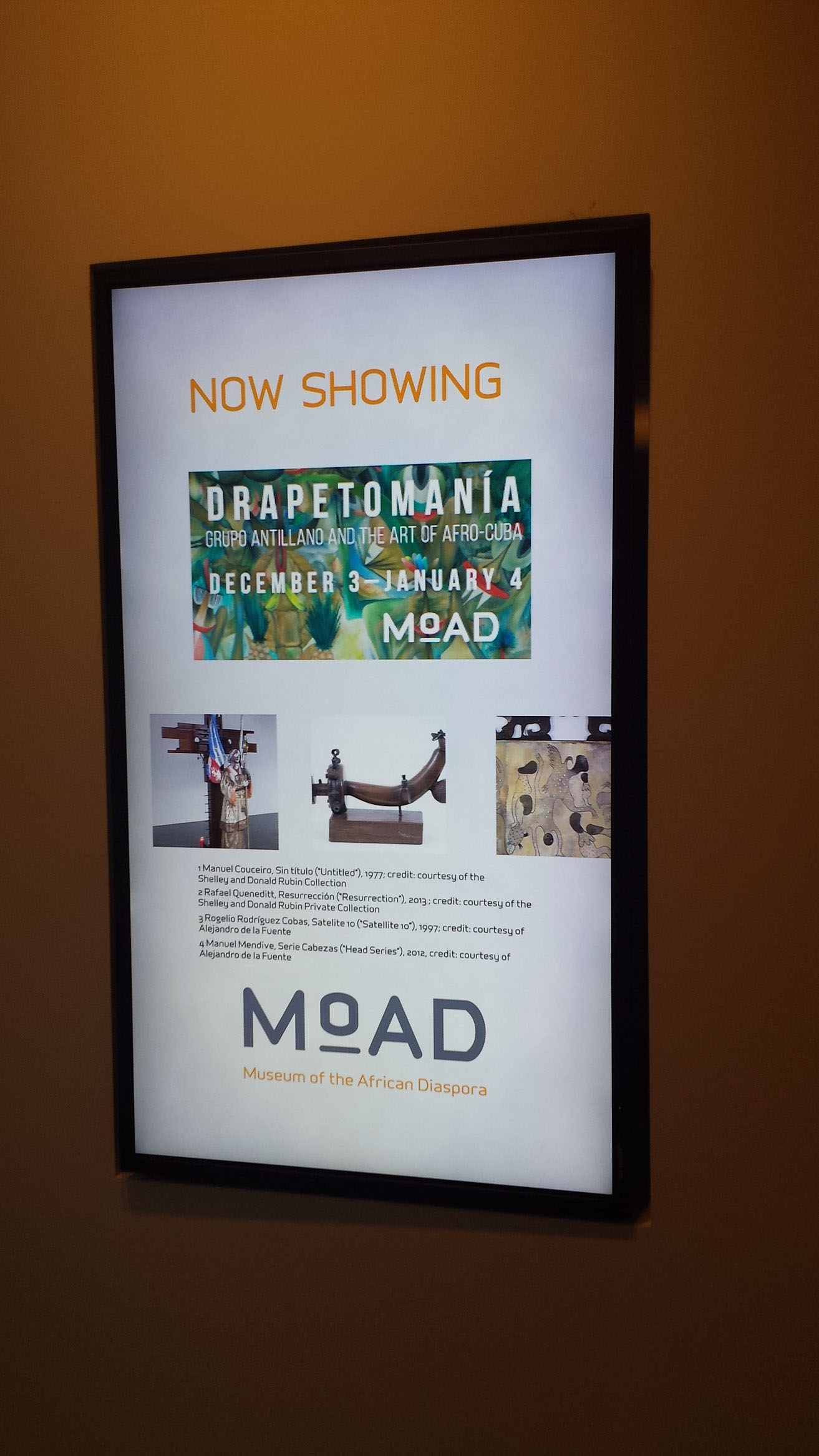

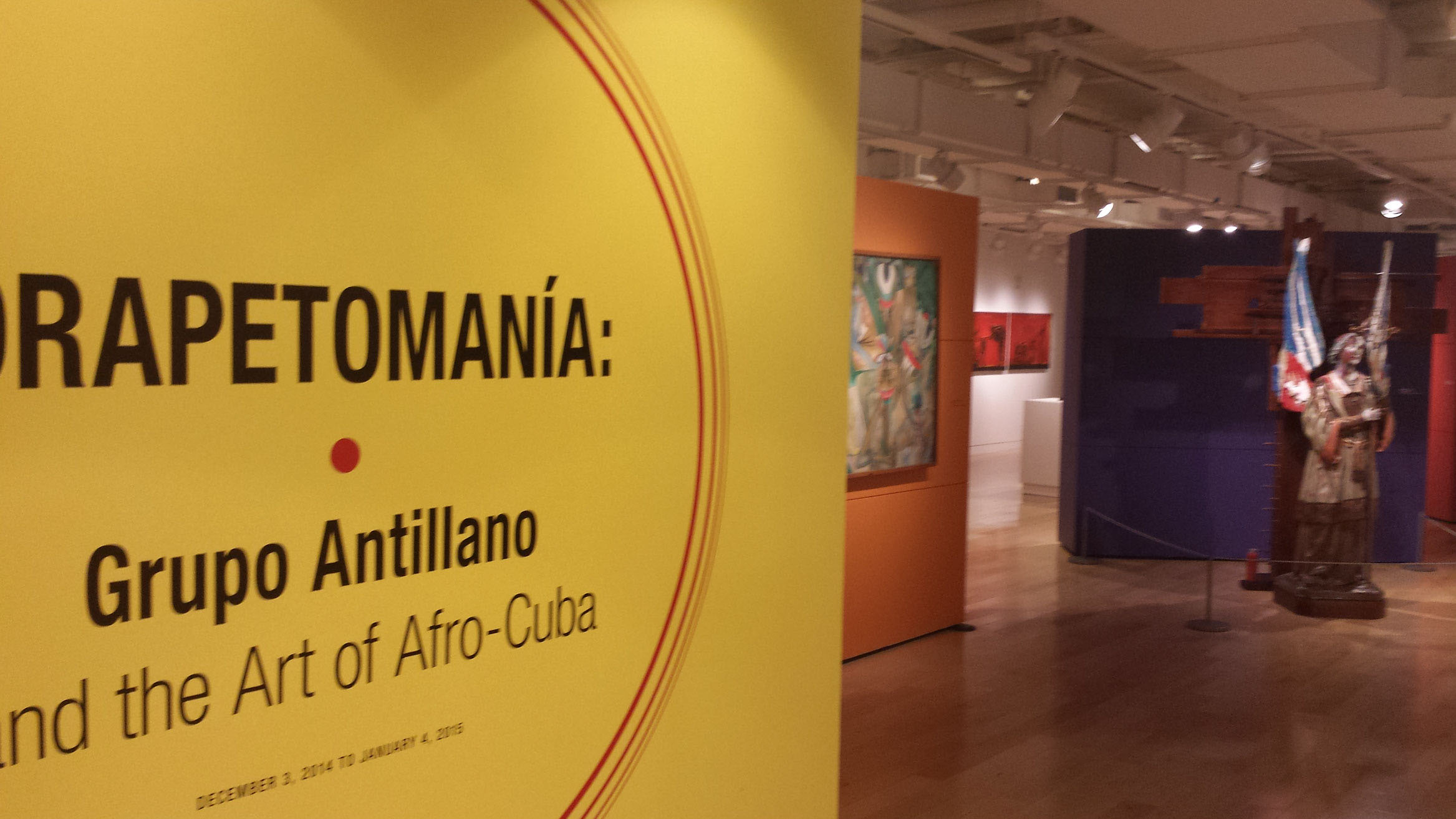

Museum of African Diaspora. MoAD, San Francisco, LA, USA

4rd Dec 2014/ , 4rd Jan 2015

The 8th Floor

NYC, NY, USA

March 7th-July 18th 2014

The African American Museum in Philadelphia, PA, USA

30th Jan / March 20th 2016

web design: Los Fieras

proyecto y curaduría:/project concept and curator: Alejandro de la Fuente

Agradecemos a la Fundación Ford por su apoyo para este proyecto /

/ Thanks to Ford Foundation for their support for this project"